Back

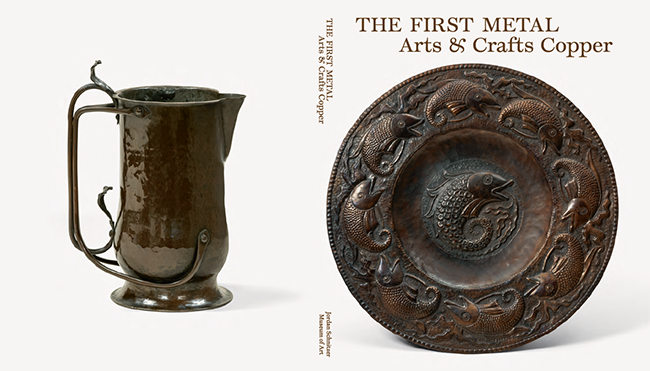

The First Metal: Arts & Crafts Copper

Jauchen, Hans

American, ca. 1918

Copper bowl with bronze leaf & seed appliqué

Copper and bronze

On Loan from Robert M. Taylor

L2022:80.7

Stickley, Gustav (attributed to)

American, ca. 1915

Box

Patinated copper

Margo Grant Walsh Twentieth Century Silver and Metalwork Collection, gift of Margo Grant Walsh

2016:12.114

Roycroft

American, ca. 1915 25

Vase

Copper

Margo Grant Walsh Twentieth Century Silver and Metalwork Collection, gift of Margo Grant Walsh

2014:38.39

Roycroft

American, 1905

Bookends

Copper

Margo Grant Walsh Twentieth Century Silver and Metalwork Collection, gift of Margo Grant Walsh

2014:38.38a,b

The First Metal: Arts & Crafts Copper

May 06, 2023 to November 03, 2024

Copper, one of the few metals that occurs naturally in a usable form, was the first metal humans fashioned into tools and accessories. For nearly five thousand years—from about 9,000 to 4,000 BCE—it was the only metal worked by humankind. From northern Iraq, where a small pendant dating to about 8700 BCE was found, to the Great Lakes region, where Native American cultures were mining and working copper more than 8,500 years ago, copper’s impact was widespread and significant. Comparatively soft, plentiful, readily mined in its pure form, and easy to shape with hand tools, copper has remained a favored material of metalsmiths to this day. The First Metal: Arts & Crafts Copper will be the first exhibition devoted solely to the use of copper in the Arts & Crafts Movement.

Drawing on the JSMA’s Margo Grant Walsh Twentieth Century Silver and Metalwork Collection and a select number of private and museum loans, the exhibition will present a range of hand-wrought copper works by many of the premier metalsmiths working in late 19th and early 20th century Britain, the United States, and beyond. The exhibition will be accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with essays by Arts & Crafts scholar-curators Mary Greensted of the United Kingdom and Jonathan Clancy of the United States.

The Arts & Crafts Movement emerged in the second half of the 19th century as a reaction against the rise of industrial labor, factories, and the profusion of cheaply-produced, machine-made goods in Britain. Its most influential proponent was William Morris, the British writer, poet, designer, and socialist. Inspired by medieval art and architecture and the writing and ideas of John Ruskin, an art critic, philosopher, and author, Morris formed the center of a circle of other like-minded artists, architects, and designers. They valued handmade objects for everyday use and believed, with Ruskin, that “self-respect derived from work and that handwork was its purest form, making better individuals and providing opportunities for creativity and human judgement,” as Greensted has noted. Morris’s decorative arts firm, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., deeply influenced British design in the Victorian era and impacted designers and architects in the United States and Europe.

For Arts & Crafts artisans and workshops, objects wrought from copper, a comparatively inexpensive “base metal,” aligned with the Movement’s commitment to producing handmade, works that were widely accessible. As Morris noted in 1878, “I do not want art for a few, any more than education for a few, or freedom for a few.” Far less expensive than gold or silver and easier to work than brass, iron, or steel, their copper works exhibited the impact of the metalsmith’s hammer, and created a visceral record of the object’s fabrication. These wares helped democratize the Arts & Crafts Movement’s ethical commitment to handmade housewares. Copper also served as a vehicle for approval prototypes that would later be made in more precious metals such as sterling silver.

Desktop boxes and humidors, bowls, vessels, trays and chargers, candlesticks, bookends, inkwells and letter openers, coffee services and other objects of daily use form the bulk of Arts & Crafts copper production. Clearly displaying the touch of the metalsmith’s hand tools, they express an artisanal world of domestic intimacy and hand wrought beauty that stands in sharp contrast to the mass-produced wares of the industrial era. Objects in The First Metal showcase the full variety of forms fabricated from copper by artisans and workshops across the United Kingdom and the United States, where Arts & Crafts ideas also took root. American artisans used the basic vocabulary of the British movement, but responded to specifically American conditions, including the influence of artisan-entrepreneurs such as Gustav Stickley and Elbert Hubbard of the Roycroft community.

Noted United Kingdom Arts & Crafts artisans and workshops represented in the show include John Pearson, A. E. Jones, Hugh Wallis, the Birmingham Guild of Handicraft, Newlyn Industrial Class, Hazelwood Studios, Arthur John Seward, George Henry Walton, and more. Along with Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops and Hubbard’s Roycrofters, the United States is represented by Joseph Heinrichs, Dirk van Erp Studio, Albert Berry, Hans Jauchen, Old Mission Kopper Kraft, and others. Arts & Crafts ideas and styles also spread across the Commonwealth and to the European continent, and the exhibition includes example of artisans working in New Zealand, Australia, and Germany.

The First Metal is organized by guest curator Marilyn Archer, working with Margo Grant Walsh as curatorial consultant. As a graduate of the University of Oregon School Architecture and recipient of the prestigious Lawrence Award, Margo Grant Walsh has been a long-time supporter of the University and of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art.

The First Metal Opening Reception and Lecture Monica Penick, Associate Professor and Associate Chair in the Department of Design, University of Texas at Austin

Saturday, May 13

Lecture: 2 p.m.

Member and Public Reception: 3 p.m.

Read more