Darcy L. Evon

From 1900 the Kalo Shop was synonymous with innovation and entrepreneurship in arts and crafts design, jewelry and metalwork. No single studio embodied the breadth of the Arts and Crafts Movement or had such a great impact on the spirit of a major city than the Kalo Shop. Its persistent quality, original designs, progressive politics and emphasis on entrepreneurship—as well as the crucial role women played in its success—made the Kalo Shop unique. The shop epitomized the philosophy of the British Arts and Crafts Movement coupled with the intensity of Chicago commerce: women entrepreneurs like Barck believed they could build profitable businesses, create jobs, promote equality for women and immigrants, and improve the conditions of working people through the new and exciting industry of hand wrought art and handicrafts.

In 1900, Clara Barck and five women designers founded the Kalo Shop after graduating from Louis Millet’s three-year design course at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC), and the shop quickly became recognized as a leader in the emerging art industries sweeping America. The women injected style and hand-crafted expertise into a multitude of otherwise mundane household and personal items, such as tote bags, wallpapers, leather accessories, lamp shades, pottery, tiles, furniture, pyrographic items, basket-weaving, textiles, embroideries, bookplates, purses, handbags, copper items and silver jewelry. Their motto was to create objects “beautiful, useful, and enduring.”

Many aspiring women artisans came and left the Kalo Shop in the early years, but Barck, who was an experienced bookkeeper and business manager from her days in Oregon, controlled the finances and built the company into a profitable enterprise. By 1903, jewelry and metalwork became more prominent when fellow artisan Mable Conde Dickson joined the partnership, and in 1904 Hanna C. Beye merged her jewelry practice into the Kalo Shop. Beye participated in many exhibitions throughout the Midwest and helped establish the Kalo Shop as a leader in innovative jewelry designs. Her diverse silver work included intricately carved, pierced, and hammered designs, sometimes decorated with enamel.

CAPTION: Hannah Christabel Beye (1879-1965) was a talented jeweler who worked with Chicago metalsmith Jessie Preston before she merged her jewelry studio into the Kalo Shop in early 1904. These necklaces show many features of early Kalo jewelry, including cutouts, cabochon stones, and geometric patterns.

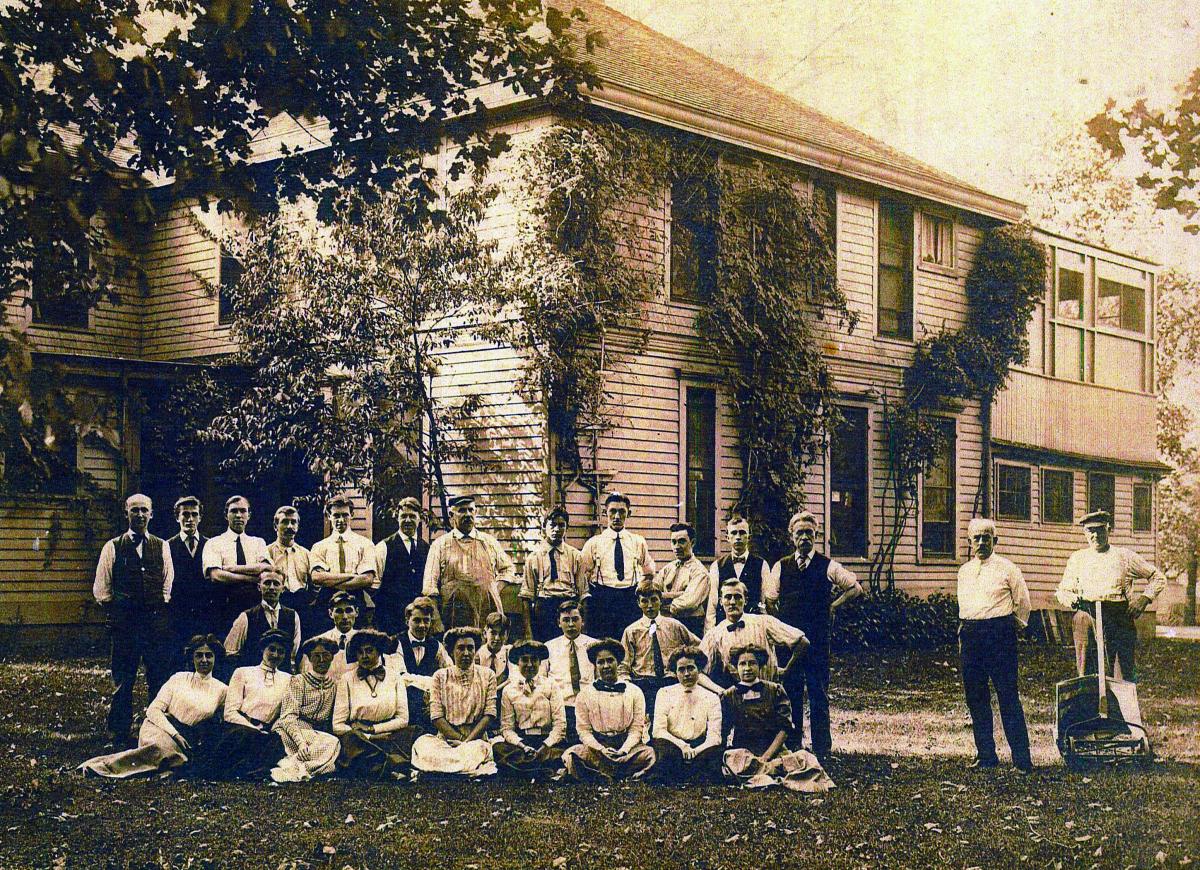

Around 1903 Barck was introduced to the inveterate entrepreneur George S. Welles by his son-in-law Frederick Richardson, who was a well-known illustrator and AIC instructor. Barck and Welles married after a two-year courtship: she was 36 and he was 57. The couple moved to suburban Park Ridge, Illinois, where Clara soon realized her dream to establish an arts and crafts school and workshop. In 1906 her sister Helena Barck left her teaching career in Oregon and bought the large, rambling farmhouse at 322 Grant Place that had been built by George Welles for his first wife, Ella Robb, but had been sold in their divorce. In 1907, the house was transferred to the Kalo Shop for stock, and Clara raised additional capital from women investors, giving birth to the Kalo Arts Crafts Community House.

In 1907, Clara Welles recruited Julius Olaf Randahl as the first professional silversmith to the Kalo Shop. He had worked at the Marshall Field & Co. wholesale hand wrought silver workshop and brought much expertise to the budding enterprise in Park Ridge. He was quickly followed by Henri Anton Eicher, a master silversmith who became the foreman of the Kalo Shop, along with jeweler Matthias William Hanck and an apprentice Henry “Dick” Sorensen. They executed hand wrought, finely crafted metalwork in hammered silver or jewelry adorned with intricate flowers, leaves, or applied monograms that would soon become the hallmark of the Kalo Shop.

Left: The first four men silversmiths and jewelers employed by the Kalo Shop, c.1908. From left to right: Julius Olaf Randahl (1880-1972), Henri Anton Eicher (1876-1923), Matthias William Hanck (1883-1955), and Henry Richard “Dick” Sorensen (1890-1991). Right: The Kalo Arts Crafts Community House and Kalo artisans, Park Ridge, IL.

As jewelry and metalwork became mainstays of the Kalo Shop, Clara Welles wanted to establish a school for aspiring women metalwork designers and jewelers at the Kalo Arts Crafts Community House. She started a school for young women apprentices; in 1908 jeweler Matthias Hanck taught the first class of 20 students. He continued teaching and making jewelry for the Kalo Shop until 1911, when Hanck started his own studio. Clara Welles turned the reins of the school over to her most promising female students, including Mildred Belle Bevis and later, Esther L. Meacham. Bevis’s design book at the AIC shows metalwork designs for jewelry, table items and small trays adorned with blister pearl.

This period at the Kalo Shop brought a plethora of nature motifs to early Kalo jewelry styles, including finely crafted flower and leaf designs surrounding natural pearls, mother-of-pearl, carnelian, chrysoprase, moonstone, turquoise, onyx, and many other semi-precious gemstones. Another main theme was geometric, cutout designs that also became iconic examples of the Chicago and American Arts and Crafts Movements.

Left: Matthias Hanck silver blister pearl brooch, c. 1912. Hanck was the first jewelry instructor at the Kalo School and taught dozens of aspiring women designers and makers in the fine art of hand wrought creations. This brooch shows the Kalo Shop’s early foray into multilayered silver frames and the beauty of natural pearls. Made at Hanck’s Art Jewelry Shop, Park Ridge, IL. Right: The Kalo Shop, silver and peridot necklace. This piece demonstrates many of the key features of early Kalo jewelry: cutout geometric design, channel set stones, and paperclip chain. Photo courtesy of Boice Lydell.

Highly distinctive and innovative features of Kalo silver hollowware, flatware, serving pieces, vases, candlesticks, dresser sets, desk sets, trays, trophies, and the like, included applied initials and interlocking monograms, hammer marks, rolled wire rims, and lobed designs.

From 1908 to 1914, the Kalo Shop in Chicago, coupled with its workshops and “school within a workshop,” in Park Ridge, exploded in popularity. Items designed and made in the Kalo workshops and school—once they met Welles’s rigorous standards, would be sold in the Chicago retail store, leading to unprecedented output. The finest silversmiths who had trained in Scandinavia, Tiffany & Co., and Gorham, as well as aspiring metalsmiths, designers and jewelers, flocked to Park Ridge to work and study at the Kalo Shop; more than 50 people were associated with the workshops. The picturesque and verdant town was transformed into a thriving and unparalleled hand wrought commercial and artistic center. In 1912, when business was booming, Clara opened a retail branch of the Kalo Shop on Fifth Avenue in New York City that was managed by her sister Helena. The lease was “Probably the highest rent for space of its size,” according to the New York Tribune. By 1913, more than 25 professional silversmiths and jewelers were employed at the Kalo workshops in Park Ridge, and many of the entrepreneurs had started their own studios and companies, making and selling wares in their off hours—with the encouragement and full support of Welles.

In 1909, East Coast silversmith J. Edward O’Marah was recruited to the Kalo Shop where he excelled at Welles’s unique arts and crafts designs; two years later, the Mulholland Brothers and Carl Henry Didrich arrived to work for the shop and teach in the Kalo workshops. In June 1911 O’Marah accepted an offer to head up the fledgling hand wrought silver business of the well-known Chicago jeweler Lebolt & Co.

In 1912 O’Marah helped transform Lebolt’s silver shop into a major player when the company was admitted to the prestigious annual arts and crafts show at the AIC. Exhibiting in the juried show was an important badge of honor for artisans from coast-to-coast. Many companies and studios considered it a triumph that put them on equal footing with the very best artisans and metalsmiths in the country. O’Marah entered works made by him, Didrich, David Mulholland, and six other silversmiths. Mulholland Brothers also exhibited on their own behalf that year and in five subsequent shows.

John Pontus Petterson worked for Gorham, Tiffany Studios, and the Jarvie Shop before launching his own company in 1913. He was a life-long friend of Kalo silversmith C.H. Didrich, and appears in several Park Ridge photographs, indicating that he was an integral part of the Chicago silversmith ecosystem and likely taught at the Kalo School. Both Petterson and Didrich had emigrated from their native Norway in 1904-05 to work for Gorham and Tiffany before they came to Park Ridge.

In 1912, the Norwegian Bjarne Becker “B.B.” Andersen moved to Park Ridge to work for the Kalo Shop and relished his close relationships with Eicher and Welles. He married the daughter of Kalo leatherworker and delivery person William Ketter. As did all of the Kalo silversmiths, he admired and respected Welles and was proud to work for a true American pioneer who had settled on a farm in Oregon with her family in the 1870s. Known for his prodigious output, Andersen crafted hundreds of items for the Kalo Shop, under his own hallmark, for the Eicher Studio, the Eicher-Andersen partnership, and the Volund Shop. His descendants have several special occasion gifts given to them by Clara Welles.

The year 1914 was a turning point for Clara Welles and the Kalo Shop. Clara was active in women’s suffrage (see Sharon Darling’s article), which was not much of a priority for George S. Welles, who preferred the life of leisure. Cracks surfaced in the marriage as Clara became more involved in Votes for Women, and in December 1912, George announced that he wanted a divorce. In the subsequent months, they maintained an uneasy reconciliation, but by February 1914, he asked Clara to file for a divorce. Clara explained it to family members: “Neither one of us had as much money as the other one thought.” George insisted on reclaiming his family abode, which housed the Kalo Arts Crafts Community and School; Clara sold it to him for $1 in May 1914, as part of their divorce agreement, and began to consolidate retail and manufacturing operations in Chicago, much to the sadness of the Park Ridge community. When the divorce was granted in June 1916, Clara asked for no alimony, telling the astonished Court that she was a businesswoman with a good income and that her husband had no business whatsoever and never had much of a business. Two months later, George died of a heart attack on the Park Ridge golf course.

The planned departure from Park Ridge in 1914 led to a flurry of entrepreneurial activity among Kalo artisans. Randahl and Hanck, who had formed the Julmat in 1911 as a side business, started their own companies in 1912: The Randahl Shop and Hanck’s Art Jewelry Shop. Randahl now moved his operations to Chicago—Hanck remained in Park Ridge and built a successful business. Sorensen established the Orno Shop in DeKalb, IL; the Mulholland Brothers opened a new firm in Evanston, IL; Edward H. Breese opened his own studio in Arlington Heights; and Esther Meacham taught and made jewelry from her own shop in Park Ridge. Clara Welles was enormously proud of these endeavors and often said that almost no one left the Kalo Shop except to start their own business.

In 1914, Andersen lived on the second floor of the Eicher barn with Kalo silversmith Daniel Pedersen and Kalo jewelers Kristoffer Haga and Grant Wood. While Andersen and Pedersen would travel to Chicago to work at the Kalo Shop during the day, Haga and Wood launched the Volund Crafts Shop out of the barn. Wood, from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, was an arts and crafts worker who became a protégé of Welles a year after she met him, when he exhibited his metalwork at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) in 1912. The Volund Crafts Shop started strong, but customers disappeared with the onset and escalation of World War I and Wood left the partnership. In January 1916, he went home to Cedar Rapids, “a ragged failure.” He returned to Chicago in 1930 to exhibit a painting in an AIC show, and won the $50 Purchase Prize for his masterpiece, American Gothic.

Copper candlesticks made by Grant Wood at the Volund Crafts Shop.

As World War I intensified, many of the Kalo silversmiths left Chicago to work in the naval shipyards in San Francisco to help with the war effort. From 1915-1920, the Kalo Shop relied on skilled Chicago metalsmith Falick Novick to supply a steady stream of popular copper bowls and silver items, including paper knives and exquisite tea sets with trays. Novick was a Russian immigrant who excelled as a metal craftsman and instructor at Hull-House, a noteworthy settlement house on Chicago’s Westside. Novick employed former Kalo silversmith Isadore Friedman, who himself was adept at the distinctive features of Kalo silver.

The Kalo Shop, with its combined retail and manufacturing facilities in Chicago, survived World War I and flourished in the post-war years with hand wrought metalwork and jewelry. As Welles often said, “Everything new eventually becomes old fashioned.” She incorporated the latest trends into metalwork and jewelry characterized by the unique Kalo style, while maintaining traditional styles that were in demand for weddings and other special occasions.

In the early 1920s, Welles bought a brownstone at 152 E. Ontario Street in Chicago as her residence, and the retail store was located in the Fine Arts Building on Michigan Avenue. When the landlord announced that the rent on the Kalo Shop would double when she renewed her lease, Welles developed a grand plan to renovate her brownstone to include her residence, the Kalo store, and workshops that would be accessible through a lush garden in the back of the home. Lowe and Bollenbacher were the architects on the project, but Welles used all of her design sense to create a splendid, multi-use estate. In her studies, she had taken a lecture class from Frank Lloyd Wright and she also studied the History of Architecture. She was proud that the design won an honorable mention in a 1923 annual architectural contest for what became known as the Clara B. Welles Building.

Before the Great Depression, Welles reported sales of $100,000 ($1.6 million in 2021 dollars), and 36 workers. Although sales fell dramatically during the economic turmoil, the Kalo Shop maintained its loyal customer base. As the largest railroad center in North America at the time, Chicago was ideal for delivering hand wrought silver from coast-to-coast, and the Kalo entrepreneurs also relied on a national customer base to sell their beautiful hand wrought wares. In 1936, Welles moved the Kalo Shop back to Michigan Avenue at 222 S. Michigan, where it survived World War II and flourished once again in the postwar years. In addition to new innovations in design, the shop maintained its traditional patterns for decades—allowing families to build large and harmonious collections over many years, and to give classic Kalo silver for wedding gifts and special occasions.

More than 20 hand wrought silver, metalwork and jewelry companies and studios grew out of the Kalo Shop, and dozens of former workers went on to teach, organize arts groups, establish vocational programs for wounded veterans, and operate their shops in many areas of the United States, spreading the Kalo influence from Midwestern states to Connecticut and as far west as California.

In 1939, Welles retired and moved to San Diego with her friend Arthur Frazer, and in 1959, she gave the Kalo Shop to its four remaining crafts workers: Robert Bower, Yngve Olsson, Daniel Pedersen and Arne Myhre. They continued to produce silver in traditional Kalo styles, as well as new, innovative themes, particularly in jewelry. A repousse circular brooch similar to those in the exhibition first appeared in a Peter Berg design book from 1926; these ever-popular items were made for decades. Most of the later designs were created by Yngve Olsson and Daniel Pedersen with strong Scandinavian influences, reflecting their heritage. In July 1970, after Pedersen retired and Olsson died, the shop closed, ending a legacy as one of the most progressive, enduring and innovative manufacturers of hand wrought jewelry, silver and metalwork from the American Arts and Crafts Movement.